On our New Zealand tour, from north to south, we see a lot of New Zealand’s landscape. Beautiful, sometimes spectacular. Perhaps the most extraordinary is Mount Cook Aoraki, New Zealand’s highest mountain and the pride and summit of the Southern Alps. We spend a night at the Aoraki Mount Cook nature reserve and go for a boat excursion on Lake Tasman to take a close (but not too close) look at the icebergs and the Tasman Glacier. Next to it are the two extraordinary, intensely blue glacier lakes, Pukaki and Tekapo.

Aoraki Mount Cook reaches a height of 3,724 metres (12,218 feet). Not long ago, it was 3,764 meters high, but then something happened in 1991.

The highest peak of the mountain collapsed—on December 14.

Join us at BKWine on our New Zealand wine tour and you will experience an exceptional excursion on the Lake Tasman glacier lake (weather permitting) and a visit to the Aoraki Mount Cook nature reserve, as well as the two spectacular lakes Pukaki and Tekapo.

Millions of tons of rock – 10 million cubic metres of rock and ice— tumbled down the mountain, reaching up to seven kilometres away from the mountain. Luckily, it is essentially a landscape without population. In fact, the rockfall occurred in such a remote area that it caused minimal damage, primarily affecting only a few glaciers. But Aoraki / Mount Cook lost 40 metres in the rockfall.

Here’s a short video that describes that event with some images of how it looks:

On our tour, we make an overnight stop at Mount Cook, a very special visit. If weather permits, we take a boat outing on the glacier lake, Lake Tasman, below the mountain, and get a close-up view of the Tasman Glacier. (In the unlikely event of rain or other impediment, that’s not possible, so a boat outing is not guaranteed.)

600-year-old ice

The Tasman Glacier begins at an altitude of 2,300 metres, which is actually 1,500 metres below the summit. Here, it receives some 20 to 30 metres of snow annually. This compacts over time into the very dense glacier ice. The entire glacier flows downhill for approximately 25 km before emptying into Lake Tasman. Only 7 km, less than a third, are visible from the lake. At the upper end, it is brilliant white, but the lower end, visible from the lake, is covered with rocks and sand. It almost looks dirty. However, this is just material that has been eroded from the rock, ripped loose by the glacier and has slowly migrated to the surface. It almost looks just like a sandy rocky mountain slope, but it is actually the surface of the glacier.

The glacier is constantly moving downwards. It is replenished at the top by the snow and finishes at the bottom as icebergs. The whole journey takes up to 600 years, so the ice that we see on the lake first fell as snow on the mountain 300-600 years ago! So, the snow that created the icebergs that you will see dates from sometime between when the first Polynesians arrived on the islands (1250–1300 CE/AD) and when the first Europeans set eyes on them (1642).

A climber’s challenge

Aoraki is a very challenging mountain to climb, with almost vertical rock faces and glaciers. It was first climbed in 1894 by three New Zealanders. The first woman to climb it was the Australian Freda Du Faur on 3 December 1910. For propriety reasons, she was not allowed to climb alone with just the mountain guide but had to be accompanied by a chaperon, and had to wear a short skirt over the trousers she wore for climbing. Sir Edmund Hillary climbed it in January 1948. (No skirt.) Eighty people have died trying to climb it.

A live illustration of climate change

The glacier lake where it ends up is called Lake Tasman after Abel Tasman, the first European seafarer to reach New Zealand, on 13 December 1642. He never went ashore.

Lake Tasman is a very recent lake. Until the 1970s, there were only a few small rivers bouncing down the mountainsides. In the 70s, they began to merge to form a larger body of water, and, aided by rockfalls, the lake was formed. Even today, the lake is still expanding, mainly at the glacier end.

The glacier in the lake is a fascinating yet also somewhat alarming illustration of climate change. When we last visited the lake, it was 500 metres longer than it had been six years earlier, when we first came to Aoraki Mount Cook. We were sitting in our small inflatable boat looking at the end of the glacier, far away, in fact, half a kilometre away, when the guide/captain said to us, “Here, where we are right now, is where the glacier ended five years ago. Now you can see the glacier’s edge over there (he points to the glacier), 500 metres away”. It was like seeing, in real time, the effects of global warming. The glacier had receded half a kilometre since we first saw it.

However, the decline of the glacier’s stretch is also accentuated by the creation of the lake. The lake itself has accelerated the glacier’s melting. Today, the glacier terminates in a long ice shelf that floats on water. Contact with water causes the ice to melt faster.

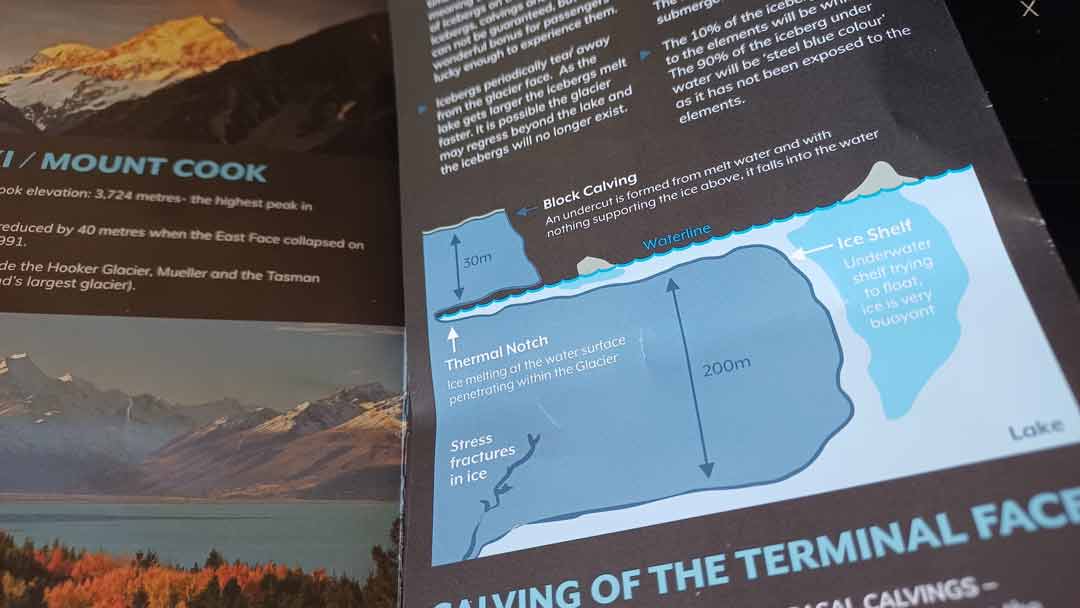

When you come to the lake, you will see a few icebergs. They are not like the Arctic ones that sank the Titanic, of course. Much smaller. They can range from a small chunk of ice to maybe a few tens of metres high. You don’t want to get too close to one of the big ones. Any iceberg can suddenly decide to turn over.

What you see above the surface is only a small part of the “berg”. 90-97% of the iceberg is below the surface. So when it decides to turn upside down, it can make a huge splash. “Berg” is actually Swedish (or ancient Scandinavian) for mountain (and ice is “is”), so iceberg literally means ice mountain. Some claim it comes from Dutch, but why would it? What icebergs do they have?

Iceberg calving

The same goes for the glacier; you don’t want to get too close, as you never know when a chunk will fall off – this is known as iceberg calving. Calving happens all the time, but it typically involves small pieces of ice breaking off and falling into the water. Or at least they look small when looking from a safe distance.

In fact, icebergs come both from above and from below. The visible part of the glacier, above the lake’s surface, is about 30 metres high, about the same height as a ten-story building. This is where you can see calving. But something hides under the surface… There’s an “ice shelf” under the surface that protrudes much, much further out than what you can see above water, up to 200 metres out. This ice shelf is a stunning 200 metres deep, seven (!) times as thick as the glacier you can see. Occasionally, big blocks of ice break loose from the underwater ice-shelf. The lake itself is estimated to be around 250 metres deep at its deepest point.

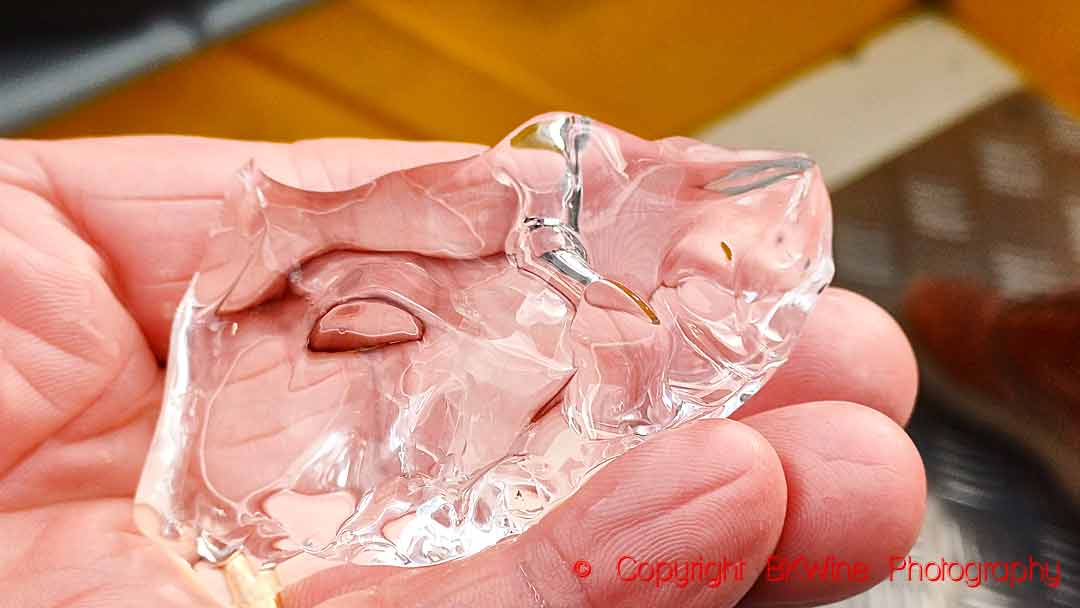

An iceberg that has just turned over looks very different from one that has been in the water for some time. It is almost transparent, clear as glass, with a blue shine—compact, clear ice. After a little while, only a few hours, it changes to the white colour that we expect of an iceberg. That’s due to air bubbles forming in the ice, changing the way it reflects light. You can see the same thing on a recently calved iceberg. The part that has been underwater still has the clear-as-glass look.

The first time we visited Mount Cook and Lake Tasman, a very large calving had occurred during the night just a couple of weeks before our visit, and the lake had an extraordinary amount of ice blocks. That was unusual. The calving had caused a big wave that travelled all the way to the other end of the lake.

To get to the jetty where the boats that take you out on the lake are, it is a good twenty-minute walk on rough terrain. But it is very well worth it. It is a very special experience.

The blue lakes and the grey water

The Tasman Lake, as well as the Pukaki and Tekapo Lakes that you pass just before arriving at the Mount Cook nature reserve, also give you a very special colour show. Starting from the top, Lake Tasman, one would perhaps think that the water in the glacier lake would be crystal clear – just melted ice. In fact, it is quite the opposite. The water is almost grey or milky. That’s because of “the glacial rock flour” in the water, a fine powder that the glacier has ground as it slides down on the sandstone, greywacke and schist rocks. It mixes with the water, and as it is still in suspension, it makes the water a milky grey.

Further downstream, when the water reaches the lower lakes, Pukaki and Tekapo, some of the particles settle and fall to the bottom, altering the way the water reflects light. This results in water that has a very special, intense blue colour at some angles, and still milky grey when close up.

You deserve an aperitif, with centuries-old ice

When returning to the Hermitage Hotel, where we stay, you definitely deserve a nice apéritif or pre-dinner drink before settling down in the panoramic restaurant. If you want a unique version of it, you can bring with you a small piece of glacier ice from the lake and chill your drink with it, as one of our travellers did. Then you have, in fact, 500-year-old snow in your gin and tonic!

Continue scrolling down for MANY MORE pictures and videos of Mount Cook and the glacier lakes.

Join us at BKWine on our New Zealand wine tour and you will experience an exceptional excursion on the Lake Tasman glacier lake (weather permitting) and a visit to the Aoraki Mount Cook nature reserve, as well as the two spectacular lakes Pukaki and Tekapo.

Approaching Mount Cook

As in many places in New Zealand, the landscape is beautiful on the approach to Mount Cook. But here it is of course particularly majestic. For the last 5 kilometres before you arrive The Hermitage Hotel (the only hotel in the nature reserve) you drive along the Lake Pukaki with its intensely blue water. As you approach, Aoraki Mount Cook increasingly dominates your view. It is breathtaking. This video takes you along the road that leads up to the Mount Cook.

Boat excursion on Lake Tasman, Aoraki Mount Cook

The boat excursion on Lake Tasman is an adventure. It starts with a long walk over rugged landscape before you board the small inflatable boats. In the boat you whizz around the icebergs under the competent guidance of the guide / captain. You will see the icebergs up-close (but not too close), the mountainsides towering on each side of the lake, a few waterfalls, and at the end of the lake the Tasman Glacier. You may see some calving, you may even see an iceberg turning over. But one can never be sure, perhaps there’s no calving and upturning (we’ve only seen it once in six years). But whatever happens on the lake, it is a majestic and magnificent experience.

The spectacle of Lake Tekapo and Lake Pukaki

You drive past the two lakes Lake Tekapo and Lake Pukaki shortly before you arrive at the Mount Cook nature reserve. But don’t just drive past. You must stop, go for a walk and wonder over the strange and beautiful water, grey and milky from one angle, amazingly intense blue from another angle. Some incredible and unlikely colours. The two lakes are surrounded by forested hills and not very high mountains, at first sight. But when you continue towards Aoraki Mount Cook the mountains rise to impressive heights.